Consultation on Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) - Defra

Summary

- 38% of UK waters are already designated as marine protected areas of one kind or another. Similarly 50% of inshore waters are subject to designated MPAs. Management measures within this network of MPAs, along with the accelerated expansion of offshore wind, represent a major displacement threat for the fishing industry.

- Ministers have made the decision to push ahead with pilot HPMAs, despite the absence of policies to deal with large scale displacement from customary fishing grounds

- An inadequate approach to evidence is apparent throughout the process of site selection for pilot HPMAs. Because the issues of cost and displacement have not been addressed adequately at site or macro level it is likely that both socio-economic and ecological harms will result.1

- Policies driven by good but incoherent intentions, and which fail to foresee and address implementation issues can have serious adverse consequences2.

- Fisheries and marine environmental protection are complex policy areas and there is clear evidence that rushing into a poorly thought-through policy can cause more harm than good. This is true for ecological damage as well as socio-economic harm.

- HPMA candidate sites show all the symptoms of a rushed shockingly superficial process that has prioritised the act of designating HPMAs as an end in itself, without seriously considering the consequences of this political theatre. With this consultation ministers have made a rash decision to push ahead with the designation of pilot HPMAs in advance of a comprehensive or coherent strategy on how to handle the forthcoming crisis of marine space. This is a mistake that will carry serious consequences.

- Steps to replace balancing competing activities and objectives with a hierarchy of prioritiesas the guiding principle of marine spatial planning are currently under way. In place of a comprehensive and coherent suite of policies to address the consequences of prioritisation, HPMAs are being introduced there in a policy vacuum.

- These five pilot HPMAs mark an initial step within policy which applies a strict dichotomy between areas reserved for nature conservation and areas necessary for food production. This contrasts starkly with the approach applied on land, where food production and environmental production are seen as complementary and intertwined objectives.

- Marine protected areas have an important role to play in protecting vulnerable habitats and species when they have clear conservation objectives, are well sited and sensitively managed on the basis of evidence. A careful, evidence and dialogue-based approach to establishing and managing a network of marine protected areas has, however, been abandoned and replaced by a rushed and inadequate process that sidesteps the elephant in the room: displacement.

- Understanding and dealing with the consequences of policy decisions is the hallmark of mature and responsible government.

- Pushing ahead prematurely with the establishment of HPMAs, in the absence of coherent policies to understand and address the wider ecological and socio-economic displacement issues raised by the trajectory of current energy and environmental policies would be reckless and irresponsible.

Displacement

At the highest level, our objection to these HPMA proposals lies in the ongoing exclusion of fishing from an increasing proportion of British waters. Both HPMA candidate sites, and wider government policies, do not take account of these wider macro level displacement issues. This is a glaring policy vacuum with the most profound potential consequences.

Source: Spatial Squeeze in Fisheries

The NFFO/SFF-commissioned report by ABPmer on the spatial pressures mounting on fishing activity provided an idea of the scale of the challenge ahead and the potential for displacement of fishing activity from customary grounds. Offshore wind and management measures within marine protected areas present the two most significand drivers of this change, yet there is no coherent government policy on how offshore energy, food security and the UK’s ambitions for marine environmental protection are to be balanced. To date there has been an assumption that fishing activity (fishers having no legal title to their production areas) can always be shifted. There is a growing awareness, however, that in addition to requiring fishing in sub-optimal locations with potentially higher fuel costs and consumption, the knock-on effects on other fisheries can be profound, albeit difficult to model.

The consultation documents state that “Analysis is on-going to understand the displacement impacts of HPMAs”. That this proposal has been put forward without analysis of its likely impact having been conducted is a shocking admission. The five HPMA candidate pilot sites are being inserted into an already complex mix before any coherent government policy to address the displacement issue has emerged. This is short-sighted and irresponsible and if pursued will deliver bitter outcomes.

Food Security

Seen in the round, the spatial squeeze will seriously limit the contribution made by fishing to the nation’s and global food security. Unlike farmers, fishers do not hold legal title to their production areas and this makes fishing uniquely vulnerable to displacement. HPMAs are but one facet of a much larger looming problem that, so far, is going unaddressed by government. Whole supply chains depend on the landing of fish and shellfish – but the consultation document has nothing meaningful to say about how marine spatial planning will deal with this radically altered production and policy landscape.

In the light of imperfect information, the HPMA programme has made a series of assumptions in selecting its preferred option, option 4, and, as a result, it adopts a process which is effectively biased against the ecosystem benefit of the provision of food.

Blue Carbon vs Increased Fuel Consumption Caused by Displacement

Sequestration of carbon is liberally sprinkled throughout the document as one of the underpinning rationales for HPMAs. Yet there is no assessment of the increased fuel consumption and carbon emissions entailed in requiring fishing vessels to steam further and for longer to make up for fishing under sub-optimal conditions.

Consultation

Stakeholder Community

It is clear that Defra ministers have, in conceiving HPMA policy, only listened to one part of the stakeholder community – the advocates of closed areas as a panacea for a range of fisheries and environmental management challenges. The answer why this is so – and why the Benyon Report panel included environmental organisations but not representatives of the fishing industry – remains an enigma.

Breach of Trust

The process of identifying marine conservation zones under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, was ostensibly a stakeholder-led exercise which gave the fishing industry a degree of confidence that protection for sensitive marine habitats would be secured whilst minimising the impact on existing fishing activities. It was understood that robust evidence and dialogue-based process would determine which fishing activities would be compatible with which conservation objectives on a site- by-site basis.

That considered, stepwise, approach has been abandoned and this amounts to a breach of trust with the many fishers who gave their time and experience to identify MCZ sites, only to see that approach abandoned and their contributions discarded.

Conservation objectives

The conservation objective for all sites is stated to be:

“To achieve full natural recovery of the structure and functions, features, qualities and composition of characteristic biological communities present within HPMAs and prevent further degradation and damage to the marine ecosystem subject to natural change.”

There are many problems with this. Having one objective for five very different sites highlights how little this process has to do with achieving specific real-world conservation outcomes. Merely claiming areas of the sea in the name of a particular political ideology is the key. Identifiable, meaningful environmental change is not even contemplated.

It is impossible to be sure what is meant by “full natural recovery”. Recovery implies reattaining some prior state, but what state and exactly how much earlier than the present are not specified. Fishing intensity is now less at some sites than it was in the past. Are we to assume then that sites are to be recovered to their state before they were commercially fished at all? In some locations that is hundreds of years ago and we have no way of knowing what those ecosystems looked like then.

Indeed, the evidence presented seems to show only the most approximate picture of what these ecosystems look like today and how they are deemed to have changed. It is hard to discern any precise baseline against which progress is to be judged. How then, are we supposed to know when this ‘objective’ has been met? When will recovery be said to have been achieved? How will we know if there has been ‘further’ degradation, particularly when the HPMAs encompass everything from the sea bed to the wave crests. Similarly, how will we judge whether ‘degradation and damage’ has been caused by ‘natural change’ (and if it is natural, we may ask why it is viewed as ‘damage’: these are living ecosystems, not sculptures) without a clear statement of the current status of all of the things that are supposed to be conserved and an understanding of the natural forces to which they are subject. The impact assessment for the sites gives estimated timeframes for habitat recovery that are mostly said to be “2-25 years”. An order of magnitude between the upper and lower estimate does not indicate either secure understanding of what the objective is or a plan for how to achieve it.

The Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009) requires any Marnie Conservation Zone order to state conservation objectives. The Act elsewhere refers to opinions being given as to the extent to which the objectives have been achieved and the steps required to be taken to achieve them. The Act clearly, therefore, anticipates that objectives should be specific and actionable. Simply to say that ‘nature must recover’ is insufficient. It is unclear where the authority to declare sweeping, indefinite closures of areas of the sea without specific reasons or objectives is claimed to come from, but the Marine and Coastal Access Act does not provide it.

The word “experiment” has been used with distressing frequency by officials discussing HPMA programme, as though seeking to make a virtue of the failure to base this process in proper evidence. The Marine and Coastal Access Act does not grant authority for experiments.

Impact Assessment

An impact assessment document has been published for this policy, but it is incomplete in several crucial respects.

The “Cost of Preferred Option” section of the summary has been left blank, with only a comment later in the document that “We estimate that costs to businesses will be between £0.006m- £9m” – a degree of uncertainty so huge as to render this estimate useless for decision making.

Section 8, of the IA document betrays a misunderstanding of how the landings system works and consequently a gross under-representation of the costs to industry, particularly the <10metre vessels.

The Registration of Buyers and Sellers[1] means that to be registered as a “landing” in the official statistics the first sale note must be offset against the purchase note of a registered buyer. This effectively excludes the whole informal sector where small quantities of fish, less than30 kg, may be sold on to individuals (or restaurants). These will be landed from inshore vessels, typically fresh and commanding the highest prices. The average prices for recorded landings will include large quantities of frozen fish which command a lesser price. In addition, it should be noted that often the inshore fleet will target Non-Quota Stocks, NQS, which do not necessarily figure in the Landing Declarations[2].

The result is a serious underestimation of the value of the fisheries and therefore of the cost of closing areas, 8.10.

Information about fishing effort is largely confined to the use of VMS data from the over 12m fleet, with only some unquantified references to spotter data for smaller vessels. This leads to a skewed view of the importance of the sites to fishing communities. Data on under 12m vessels is available: from landings declarations, for example, or simply by going to ports and asking for it. Offshore developers have been doing this for years, when assessing the impact of their projects and compensating those adversely affected by them, so why not do it in this case?

The impact assessment’s description of the policy context does not include any reference to the Fisheries Act or the Joint Fisheries Statement. It is hard to see how a significant fisheries management initiative such as this can be evaluated without any reference to those clear and unambiguous statements of law and policy governing this area.

There are repeated references to conducting a fuller impact assessment after the conclusion of the present consultation. Surely, though, consultees cannot give meaningfully informed responses if the likely impact of the proposals hasn’t been assessed. The same could be said of the repeated promises to evaluate the effects of displacement. It is shocking that a process which claims to be based in evidence can state that “Analysis is on-going to understand the displacement impacts of HPMAs”. If the impacts of the proposed measure have not yet been studied, how can these radical measures be imposed? Livelihoods are at stake and yet are treated as an afterthought.

To state that a decision will first be taken and its implications examined later is entirely inconsistent with principles of integrity, objectivity and accountability that lie at the heart of good governance. Far from a proper impact assessment, much of this document reads like an attempt to gather the information that, according to the Benyon Review, should have been collected before the selection of sites was first made.

Site Level Assessments

The consultation exercise so far has made clear that ministers are preparing to make decisions on the flimsiest information, extracted from broad-scale existing data sources, rather than comprehensive site-level surveys. This is true of both ecological and socio-economic data used to prepare the short-list of candidate sites. This has been referred to during the various consultation meetings as a google earth approach to evidence. When peoples’ livelihoods are on the line this is not good enough. Neither is it adequate to rely on a 12week consultation to fill the gaps.

The fishing industry and the wider public should have confidence that the effort has been taken to understand what is at stake, and what it is that HPMAs are for.

Given the scale at which ecological and socio-economic evidence has been gathers so far (the “google earth approach”) it will be of the utmost importance to collate evidence at site level, prior to making any definitive decisions.

It is absolutely essential that the views of the fishing industry at site level are fully taken account because it is here that some idea of the impact of the current policy approach can be understood. A cosmetic box-ticking consultative exercise will not suffice.

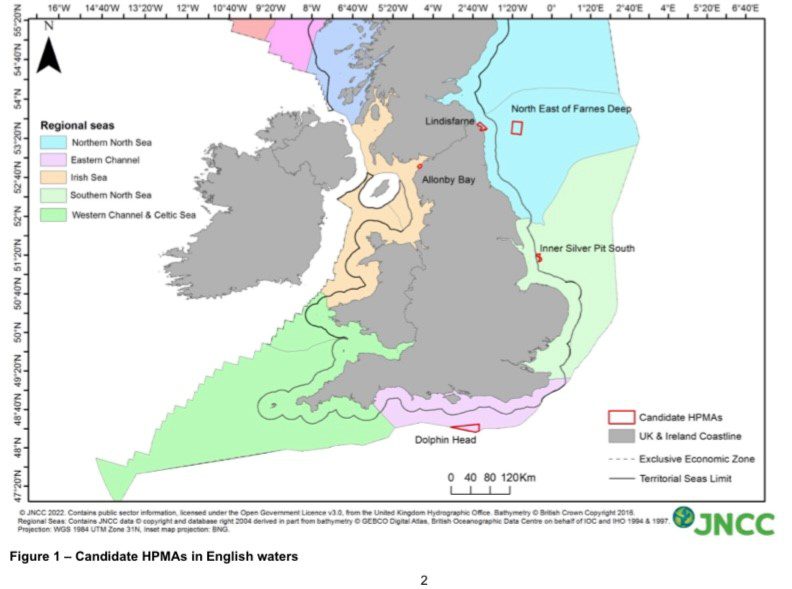

Allonby Bay

The impact assessment wrongly identifies this site as being in the Northumberland IFCA region. It is impossible to know whether the failure to correct this glaring error before publication is the result of a lack of understanding, or a lack of care – and difficult to decide which is worse.

It is profoundly worryingly that “recovery timeframes were not assessed for this site”. This statement is suggestive of a very incomplete understanding of both the status of the site and the aim of establishing an HPMA there. Why has the site even been included in this proposal if the assessment has not been completed?

Bafflingly, we are told that “With limited disturbance in this area, Allonby Bay represents a relatively natural ecosystem”. The report seems to have concluded that fishing there is doing no harm, in which case why is it being proposed to ban it? There is simply no proposed link between the conservation objective – such as it is – and the contemplated conservation action. Furthermore “Impact [of a fishing ban] on local communities could be significant” because the vessels operating there have a high degree of reliance on the site. If fishing is not adversely affecting the ecosystem and to ban it would cause significant economic harm to local families, how can such a step possibly be contemplated?

Lindisfarne

The inadequacy of the site information and the impact assessment process are starkly demonstrated by the proposed Lindisfarne site. Given the displacement effect and knock-on consequences and solid opposition from the local community, it is inconceivable to us that Lindisfarne could be designated as a HPMA.

All of the general concerns regarding displacement apply here.

North East of Farne Deeps

Although not the most heavily fished areas off the North East coast, two reasons present themselves as reasons why designation of NE of Farne Deeps would be misconceived:

- It is recognised that the impact of fishing on the ecology of the area has been negligible

- Displacement of the fishing activities that do occur in the area will concentrate impacts in other areas leading to potential ecological degradation and socio-economic impacts there, including some near-shore zones

Dolphin Head

It is the absence of a coherent government policy to account for and deal with the displacement effects of vessels which currently work in this area that is the principal reason why designation as an HPMA would be a stepping stone to socio-economic and ecological harms.

The failure to consider shipping when proposing to create a HPMA at Dolphin Head is a bewildering omission. The sea’s surface is listed as a conservation feature and yet the high volume of shipping passing through the site is ignored. It seems clear that some sectors are being privileged in this process, while fishing is targeted.

Not only is this region already heavily used and host to a variety of infrastructure developments, it is also the location of our most significant maritime interactions with EU member states, with all of the post-Brexit complexities that entails. Should an HPMA be imposed on this already convoluted situation, the neglected issue of displacement will prove especially disruptive.

We strongly endorse the comprehensive consultation response submitted by the South East Fishermen’s Protection Association which raises a multitude of valid and unanswered questions regarding this site and the Government’s HPMA policy generally.

Silver Pit

The Silver Pit has been fished since the mid-nineteenth century. It cannot seriously be suggested that we can know what this ecosystem looked like before its use by humans became firmly established. What purpose is served by stopping food production in an area where it has been conducted for 170 years?

Moreover, the environmentally deleterious consequences of displacement will be particularly severe in this location. Historically, it has primarily been fished with mobile gear, by French, Scottish and southern English boats. The surrounding shallow waters are extensively fished by the local potting fleet. A longstanding agreement between mobile and static gear fishermen has ensured that these two sectors have coexisted successfully for decades.

Imposing an HPMA here would displace the mobile gear boats onto the surrounding shallow ground, in an attempt to recoup some of their economic losses. Bottom trawling effort would, therefore, be displaced from a location where it has occurred continuously for generations and onto a region where it has never taken place. If fishing activity is causing ‘degradation’ as claimed, this measure will not reverse it: it will substantially increase it.

Fisheries management

For all these sites then, we are not certain what the current ecosystems contain; we are not clear about what they ought to look like; we cannot state what steps must be followed to bring about the desired change; and we will not know when the endpoint has been reached. Seemingly the only thing that can be specified about these HPMAs is that fishing must be stopped.

It is clear that the sites have been selected so as not to interfere with the operations of some marine users (offshore wind, shipping, aggregates dredging). The desire to conserve the marine environment has been conditioned by a reluctance to engage with industries perceived as having greater national strategic significance. We submit, however, that food production – both for the UK population and for export – and the provision of jobs in coastal communities, are worthy of equal consideration. Instead, this whole process is predicated on an assumption that some industries are more important than others – indeed, are more important than marine conservation – and must be prioritised.

This does not look like a conservation measure: it looks like a fisheries management measure. As such, it is entirely inconsistent with the promise in the Fisheries Act 2020 that “the management of fish and aquaculture activities is based on the best available scientific advice”. It also fails to respect the commitment in that Act that fisheries management should be conducted through the development of a Joint Fisheries Statement.

The process being followed looks like an attempt to circumvent the careful, considered and collaborative decision making process envisaged in the draft JFS (“The use of best available evidence and scientific advice, transparent decision making, and partnership working, will be core principles that will underpin delivery”) and instead to privilege the views and demands of an unrepresentative constituency far removed from the locations that will be subjected to these new under-the-radar fisheries management regimes and the views of the people who live and work there.

Conclusion

We can only speculate on why the Government has decided to push ahead with pilot HPMAs armed with little more than good intentions. The thrust of our response is that good intentions on their own are not enough, and there is sufficient reason to understand that the fishing industry will be harmed by the displacement generated by this premature and ill-considered initiative.

The present government’s emphasis on securing food security and economic viability, sits very incongruously with a marine policy approach that will undermine both.

Notes

- When the scientific community evaluated the effects of a seasonal closure of a large area of the Northern North Sea in 2004, it concluded that:

- The measure had made little difference to the spawning stock biomass because much of the uncaught cod was caught outside the closed area or after the seasonal restriction had been lifted

- The Dutch beam trawl fleet had been displaced onto pristine ground previously unfished

- The Scottish demersal fleet was forced to work on grounds full of immature haddock, where there was an exceptionally high level of discards as a result

- There is a direct parallel between the Government’s current policy on HPMAs and the EU landing obligation adopted in 2013, which was similarly driven by good intentions but skated over the practical implementation issues, in a rush of legislative exuberance and political opportunism. The evidence suggests that overall discard rates per trip for all quota species was higher in 2019 than in previous years in the North Sea, Irish Sea and Celtic Sea. This indicates that the same or greater % of the catch is being discarded under full implementation of the landing obligation than beforehand.

http://randd.defra.gov.uk/Document.aspx?Document=15357_MF1262_English_catch_and_discard_patterns_during_phased_implementation_of_the_Landing_Obligation.pdf In other words things have been made considerably worse.

[1] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2005/1605/contents

[2] Note that NQS accounted for c.50% of the value of English fisheries in 2019 – MMO, UK Sea Fisheries Statistics.